Remote Work for Employees with Disabilities: Will Pandemic Changes Stick?

Becky Beach has been struggling with mental illness since she was 18 years old. With bipolar disorder and severe anxiety disorder, it’s always been difficult for her to work in an office setting. “I would use up my sick days every year. I even went over the number of days I could call in sick so my pay was docked,” she says.

When the pandemic started and everyone was able to work from home, it was like a godsend for Beach and others like her. “It made me so much more productive. I didn't have to waste time in a 45-minute commute each way any longer. I found I stopped having panic attacks and mood swings, so I did not use any sick days at all,” says Beach.

For over a year, she finally knew what it felt like to be able to do her best work.

For people with disabilities (PWD), the pandemic finally validated what many in the community have been saying for years: that remote work can in fact be productive. Yet many were disappointed that it took a pandemic to give them the chance to prove it, as revealed by a joint report by Brandwatch and Monster. That’s because before, when PWD asked for accommodations to work from home, even among those who filed lawsuits, it was typical for them to be turned down, says Douglas Kruse, professor and co-director of the Rutgers Program for Disability Research in the School of Management and Labor Relations at Rutgers University. “Understandably, it’s built up a little resentment that they had been asking for this for years and now suddenly it was possible.”

Nevertheless, advocates and PWD are hoping that the success of remote work has cracked the door open to new possibilities. “What the pandemic has done is really shake up the structure of most workplaces and really caused employers to rethink how jobs get done,” says Kruse. “It’s a good thing for PWD when employers are thinking hard about how essential tasks get done because that leads to more creative solutions. You don’t have to have people fit the jobs; the jobs can be structured around the people.”

Unfortunately, according to Monster’s Future of Work survey, although flexible work schedules and remote work were the most frequent policy changes made during the pandemic, only 44% of employers planned to make the changes permanent. And many have already started scaling back and returning to in-person work.

We connected with some people with disabilities who shared how remote work and shifting employer policies has worked out for them so far. Their answers may surprise you.

Spotlight on new accommodations

When most people think about disability accommodations, they think about office design and physical structures like ramps for wheelchairs. But the pandemic revealed a big need for technology accommodations, too – including for those who set up home offices for the first time during the pandemic. Luckily, some employers have stepped up.

“Transitioning to a remote world has made my work life even more accessible over the last 18 months,” says Moeena Das, Chief Operating Officer at the National Organization on Disability (NOD), who is deaf. Having access to regular captioning, whether automatic or provided by a transcriber has been essential, she says, while communicating via chat/instant messaging has made it easier to participate in ad-hoc conversations.

On the flip side, it’s not perfect. “Automatic captioning, which is AI-based, is not perfect and depending on the software, critical information can be communicated incorrectly or be missed entirely,” she says. “And, there can be more visual exhaustion on my part, especially in situations where one is focusing on following captions, lipreading and screen-sharing when relevant – all on the same screen.”

That said, navigating the challenges of in-person work during Covid has been difficult, says Das. “Speaking from my own experience, I cannot understand what’s being said when folks are wearing masks, as I lose the ability to lipread and follow facial expressions and other nonverbal cues – something which can cause great anxiety in thinking about transitioning back to in-person settings.”

Lauren Weishaar, manager of deaf and hard of hearing employment services for Easterseals New Jersey, has had a similar experience. “Anytime I have an in-person training or meeting, I will need to request either a sign language interpreter or closed captions,” she says. She also passes out masks with a clear window opening to presenters. “Everyone has been so kind and understanding in utilizing the tools I need to ensure I have full access at work,” she says.

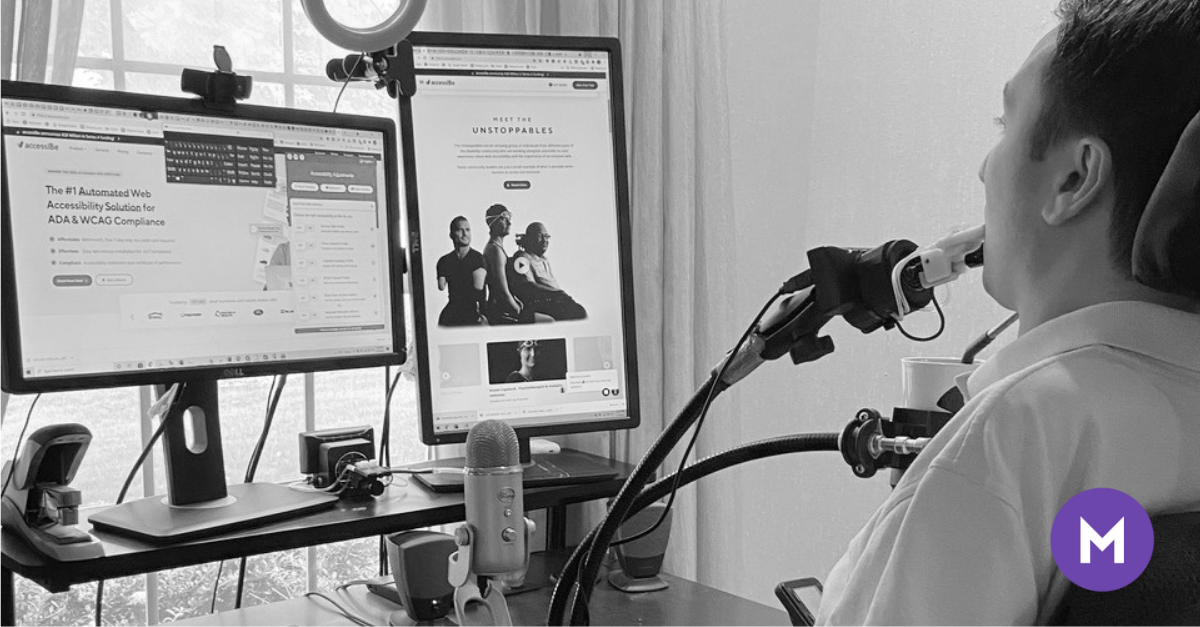

With Covid forcing many people to work remotely, web accessibility on the Internet has become another hot topic. “It breaks my heart every time I have to share the fact that less than 2% of the Internet meets accessibility guidelines,” says Josh Basile, C4-5 quadriplegic, lawyer and community relations manager for accessiBe, a web accessibility company. This can include low contrast text, a lack of alt tags on images that explain what the image is, and more.

“If 98% of city streets and businesses remained inaccessible, people would be losing their minds. The Internet must be more accessible to all abilities to allow people with disabilities to be welcomed and not to be sidelined,” says Basile.

Managing disabilities from home

For Shari W., a speech teacher for the New York City Department of Education, being remote made it easier to cope with her rheumatoid arthritis since it removed three hours of daily commute time from her day. “RA tends to make you feel exhausted, especially if you are in a flare. The extra sleep and no commute kept many of my symptoms at bay. I definitely was able to take better care of myself working from home.”

Working remotely has also been a boon for some individuals with ASD (Autism Spectrum Disorder). “I can stay productive while ensuring my own home environment is safe and without worry of stimuli that might cause me to shut down,” says Christian Donovan, packing engineer at The Hershey Company. Even better? “I don’t have to worry about my “quirks” causing issues with new people I meet because most are hidden when I work from home,” he says.

But not all PWDs prefer to work from home. “One thing that I miss most working in-person is being fully seen,” says Basile. “Usually when I enter a meeting the first thing a person sees are my power wheelchair wheels and then next, they hear my voice and mind. I like wheeling down the street or entering into a meeting and letting my disability be clearly visible.” As an advocate, he says being in person and surrounded by colleagues does a lot of good to bring about disability awareness within the workplace more so than working remotely.

Being “out of sight, out of mind” can create a new set of challenges, agrees Kruse. “We do know from data sets that people who do home-based work tend to be paid less. And it can be a special problem for PWD who might not be part of workplace culture in the first place,” says Kruse.

It was good while it lasted

Many jobs like Shari’s are already back to an in-person, full-time schedule—and that has been challenging. “I have so much more pain from the sitting and driving again. My anxiety is sky high being around so many people daily, and I am not sleeping well,” she says.

The same goes for Beach who was disappointed when she recently learned that her company was making it mandatory for all employees to go back to the office at least two days a week. “I tried my best, but it was even more difficult for me to manage,” she says. “I was so used to working from home and being with my pets, my emotional support animals, that I couldn't function in the office at all.” Ultimately, she decided to quit the job in order to focus on her blog and eCommerce store, MomBeach.com, a work-at-home resource for moms.

Many PWD were left behind in the remote work revolution

In all the talk about remote work and PWD, the reality is that only 1 out of 5 people with disabilities started working from home during the pandemic — mostly office workers, managers, and others in white-collar roles, according to a report by the Rutgers Program for Disability Research. That’s because workers with disabilities are disproportionately likely to be in blue-collar and service jobs (46.6% compared to 37.7% of other workers), which are not amenable to telework. As such, the majority of workers with disabilities were left behind in the rapid expansion of telework.

“While remote work can be a great opportunity to PWD, we also need to make it easier for them to get into those jobs in the first place,” says Lisa Schur, professor and co-director of the Rutgers Program for Disability Research. “More needs to be done.”

For example, a bigger emphasis on virtual recruiting tools over the past few years, and especially during the pandemic, could inadvertently be filtering out potential talent. If an online application system is not accessible, or there are personality tests that aren’t designed to be inclusive of applicants with neurodiversity, many people with disabilities will not even make it past the initial candidate screening.

It’s no wonder that in the Brandwatch report, hiring practices, barriers to employment, and ways to improve job searches and application processes were the key conversation drivers on social media among PWD.

PWDs are often last on the diversity priority list

Monster research shows that only 7% of employer diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) strategies focus on disability. That aligns with what one Twitter user shared: “Three areas of inclusion that often get forgotten or ignored in discussions around DEI: Disability, age and neurodiversity."

In fact, as the Delivering Jobs campaign (which encourages companies to hire and support neurodiverse employees) points out, approximately eight out of 10 adults with autism or intellectual or developmental differences in the U.S. do not have a paid job despite having the skill sets and expertise required.

What’s next?

So are the days of remote work for PWD numbered? Not necessarily. Some employers are embracing the fact that workplace flexibility can give them access to more diverse talent, and increase satisfaction among current employees. Such forward-thinking organizations probably realize that hiring workers with disabilities has business benefits: one study by Accenture has such companies outperforming their competitors with an average of 28% higher revenue.

What’s more, the current talent shortage is forcing employers to think more creatively and strategically about sourcing, and puts job seekers and employees in a better position to negotiate for remote work options.

As for employers that want to include PWD in their DEI efforts, they can start with a couple of simple steps: Ensuring that their career site and application process is accessible, using appropriate language in job postings, and extending remote and flexible working options beyond the pandemic. But most important, is listening – really listening – to the needs of the PWD community, and then taking concrete action to accommodate them.

Want to dive deeper into the the changing conversations around people with disabilities at work and ensure your hiring practices are inclusive of PWD? Check out our resource center to learn more.

Trial Attorney at Jack H. Olender & Associates I Community Relations Manager at accessiBe I United Spinal Association Board Member

2yThank you so much for spreading the word about the importance of employing persons with disabilities! The pandemic has confirmed that remote work works for all abilities. Workers with disabilities are natural problems solvers and can contribute to the workforce in meaningful ways in many different settings 😀

A special thanks to Doug Kruse & Lisa Schur from Rutgers University, Moeena Das from the National Organization on Disability, Lauren Galgano-Weishaar from Easterseals New Jersey, Josh Basile from accessiBe, and Becky B. who helped make this story possible!